Gravitational Waves. How were they discovered?

A little more than a billion years prior, a large number of systems from here, a couple of dark openings impacted. They had been surrounding each other for ages in such a mating dance, gathering pace with each circle, tearing consistently nearer. When they were two or three hundred miles separated, they were whipping around at almost the speed of light, delivering extraordinary shivers of gravitational energy. Existence became misshaped, similar to water at a moving bubble. In the small part of a second that it took for the dark openings to at long last consolidation, they emanated multiple times more energy than every one of the stars in the universe joined. They shaped another dark opening, multiple times as weighty as our sun and nearly as wide across as the territory of Maine. As it streamlined itself, expecting the state of a somewhat smoothed circle, a couple of last bunches of energy got away. At that point reality became quiet once more.

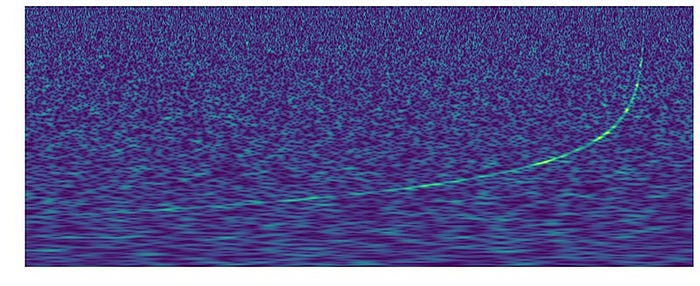

The waves undulated outward toward each path, debilitating as they went. On Earth, dinosaurs emerged, advanced, and went terminated. The waves continued onward. Around 50,000 years prior, they entered our own Milky Way world, similarly as Homo sapiens were supplanting our Neanderthal cousins as the planet’s predominant types of chimp. 100 years prior, Albert Einstein, one of the further developed individuals from the species, anticipated the waves’ presence, motivating many years of theory and pointless looking. 22 years prior, development started on a gigantic finder, the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (ligo). At that point, on September 14, 2015, at not long before eleven AM, Central European Time, the waves arrived at Earth. Marco Drago, a 32 year-old Italian postdoctoral understudy and an individual from the ligo Scientific Collaboration, was the principal individual to see them. He was sitting before his PC at the Albert Einstein Institute, in Hannover, Germany, seeing the ligo information distantly. The waves showed up on his screen as a packed squiggle, yet the most wonderful ears known to mankind, receptive to vibrations of not exactly a trillionth of an inch, would have heard what space experts call a tweet — a weak challenging from low to high. Earlier today, in a question and answer session in Washington, D.C., the ligo group declared that the sign comprises the main direct perception of gravitational waves.

At the point when Drago saw the sign, he was paralyzed. “It was hard to comprehend what to do,” he advised me. He educated an associate, who had the common sense to call the ligo tasks room, in Livingston, Louisiana. Word started to flow among the thousand or so researchers associated with the venture. In California, David Reitze, the leader overseer of the ligo Laboratory, saw his little girl off to class and went to his office, at Caltech, where he was welcomed by a blast of messages. “I don’t recollect precisely what I said,” he advised me. “It was thusly: ‘Good lord, what is this?’ “ Vicky Kalogera, a teacher of physical science and stargazing at Northwestern University, was in gatherings throughout the day, and didn’t hear the news until dinnertime. “My better half requested that I put everything out on the table,” she said. “I was totally overlooking him, skimming through every one of these unusual messages and thinking, What is going on?” Rainer Weiss, the 83 year-old physicist who initially recommended fabricating ligo, in 1972, was holiday in Maine. He signed on, saw the sign, and shouted “My God!” noisily that his better half and grown-up child came running.

The teammates started the challenging interaction of twofold , triple-, and fourfold checking their information. “We’re saying that we made an estimation that is about a thousandth the measurement of a proton, that informs us regarding two dark openings that converged over a billion years prior,” Reitze said. “That is a lovely uncommon case and it needs phenomenal proof.” In the interim, the ligo researchers were committed to supreme mystery. As bits of gossip about the discovering spread, from late September as the week progressed, media energy spiked; there were thunderings about a Nobel Prize. In any case, the colleagues gave any individual who got some information about it a condensed variant of reality — that they were all the while investigating information and had nothing to declare. Kalogera hadn’t disclosed to her better half.

Ligo comprises of two offices, isolated by almost nineteen hundred miles — around a three-and-a-half-hour trip on a traveler fly, however an excursion of under ten thousandths of a second for a gravitational wave. The finder in Livingston, Louisiana, sits on swampland east of Baton Rouge, encircled by a business pine woods; the one in Hanford, Washington, is on the southwestern edge of the most defiled atomic site in the United States, in the midst of desert sagebrush, tumbleweed, and decommissioned reactors. At the two areas, a couple of solid lines approximately twelve feet tall stretch at right points into the distance, so that from high over the offices take after craftsman’s squares. The lines are so long — almost more than two miles — that they must be raised starting from the earliest stage a yard at each end, to keep them lying level as Earth bends underneath them.

ligo is important for a bigger exertion to investigate one of the more slippery ramifications of Einstein’s overall hypothesis of relativity. The hypothesis, set forth plainly, states that reality bend within the sight of mass, and that this arch creates the impact known as gravity. At the point when two dark openings circle one another, they stretch and crush space-time like kids going here and there aimlessly on a trampoline, making vibrations that movement to the very edge; these vibrations are gravitational waves. They go through us constantly, from sources across the universe, but since gravity is such a ton more fragile than the other principal powers of nature — electromagnetism, for example, or the associations that tight spot a particle together — we never sense them. Einstein thought it profoundly impossible that they could at any point be recognized. He twice pronounced them nonexistent, turning around and afterward re-switching his own expectation. A doubtful contemporary noticed that the waves appeared to “spread at the speed of thought.”

Almost fifty years passed before somebody set about building an instrument to identify gravitational waves. The primary individual to attempt was a designing educator at the University of Maryland, College Park, named Joe Weber. He considered his gadget the full bar radio wire. Weber accepted that an aluminum chamber could be made to work like a chime, intensifying the weak strike of a gravitational wave. At the point when a wave hit the chamber, it would vibrate marginally, and sensors around its periphery would make an interpretation of the ringing into an electrical sign. To ensure he wasn’t recognizing the vibrations of passing trucks or minor seismic tremors, Weber built up a few protections: he suspended his bars in a vacuum, and he ran two of them at a time, in separate areas — one on the grounds of the University of Maryland, and one at Argonne National Laboratory, close to Chicago. In the event that the two bars rang similarly inside a small portion of a moment of one another, he closed, the reason may be a gravitational wave.

In June of 1969, Weber reported that his bars had enlisted something. Physicists and the media were excited; the Times announced that “another section as man would see it of the universe has been opened.” Soon, Weber began detailing signals consistently. Yet, question spread as different research facilities fabricated bars that neglected to coordinate with his outcomes. By 1974, many had presumed that Weber was mixed up. (He kept on guaranteeing new identifications until his demise, in 2000.)

Weber’s heritage molded the field that he set up. It made a toxic discernment that gravitational-wave trackers, as Weiss put it, are “all liars and not cautious, and God knows what.” That insight was supported in 2014, when researchers at bicep2, a telescope close to the South Pole, identified what appeared to be gravitational radiation left over from the Big Bang; the sign was genuine, yet it ended up being a result of grandiose residue. Weber likewise left behind a gathering of analysts who were inspired by their powerlessness to recreate his outcomes. Weiss, disappointed by the trouble of training Weber’s work to his students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, started planning what might become ligo. “I was unable to comprehend what Weber was doing,” he said in an oral history directed by Caltech in 2000. “I didn’t think it was correct. So I concluded I would go at it myself.”

In the quest for gravitational waves, “a large portion of the activity happens on the telephone,” Fred Raab, the top of ligo’s Hanford site, advised me. There are week by week gatherings to talk about information and fortnightly gatherings to examine coördination between the two indicators, with teammates in Australia, India, Germany, the United Kingdom, and somewhere else. “At the point when these individuals awaken in the late evening dreaming, they’re dreaming about the locator,” Raab said. “That is the manner by which cozy they must be with it,” he clarified, to have the option to make the incredibly intricate instrument that Weiss imagined really work.

Weiss’ recognition technique was by and large not quite the same as Weber’s. His first understanding was to make the observatory “L”- molded. Picture two individuals lying on the floor, their heads contacting, their bodies shaping a correct point. At the point when a gravitational wave goes through them, one individual will develop taller while different therapists; after a second, the contrary will occur. As the wave extends space-time one way, it fundamentally packs it in the other. Weiss’ instrument would check the contrast between these two fluctuating lengths, and it would do as such on a colossal scale, utilizing miles of steel tubing. “I would not have been distinguishing anything on my tabletop,” he said.

If you think this is interesting, click here to read about Water Powered Generators.